Finding T2-711: the First Me-262 at Wright Field

By Robert L. Young

Historian

National Air and Space Intelligence Center

18 December 2013

INTRODUCTION

When the German Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter entered combat in April 1944, the world changed forever. Although the aircraft exhibited many shortcomings, some through design and others through late war production, the Luftwaffe’s Me-262 represented the beginning of the end for propeller-driven fighter aircraft. The Germans began the design work on the aircraft in April 1939, with an effort known as Design P1065. In the next couple of years, Messerschmitt finished the design work and built prototypes, although due to slow jet engine development the first design had a propeller with a nose-mounted Junkers Jumo 210 engine. On 18 April 1941, the prototype Me-262 V1 flew for the first time with a propeller. Another difference from the later production models was the prototype’s conventional tail-dragging landing gear design. The prototype did feature a technological breakthrough that influenced future aircraft design: the swept wing.

The unreliability of early turbojet engines manifested itself from the beginning. The Messerschmitt team wisely kept the Jumo 210 mounted for the first test flight of the Me-262 V1 with the new BMW P 3302 jet engines. On the 25 March 1942 test flight, both turbojets failed immediately after takeoff and the pilot, Fritz Wendel, used the piston engine to land. After Junkers delivered two prototype Jumo 004 jet engines early in July 1942, the Me-262 V3 prototype first flew as a pure jet aircraft on 18 July. Although the Jumos worked better than the BMW engines, they had very short operational lives, typically lasting only 12-25 hours. Even with the short engine life, the jet presented a revolutionary jump in technology that went misunderstood by German leadership.

Although the Me-262 flew faster than any Allied fighter, Hitler’s vision for the aircraft was for it to serve as a high-speed bomber. He ordered the design modified to carry a 1,100-pound bomb load for the purpose of attacking England. It never fulfilled that fantasy mission and the German pilots believed the emphasis on a bomber version slowed the production of fighter variants. Only when it proved effective in countering airstrikes did the nation’s leader allow it to fully fulfill the interceptor role. The fighter version went into full production in November 1944. By then it was too late. Because of Allied bombing on production facilities, the Me-262 manufacturing effort remained in small factories in Germany that only produced about 1,430 examples. Because of engine manufacturing shortfalls, only about 200-300 ever reach full operational status. Between the slow development of the engines and Hitler’s misuse of the revolutionary airframe, the Luftwaffe never got the opportunity to use the Me-262 to its full potential and it remained a mere footnote in the annuals of air combat.

The Me-262 did not significantly change the course of the war for Germany. According to its designer, Willy Messerschmitt, it came too late and lacked reliable engines. Yet, the fact that jets saw combat in World War II and placed fighter pilots and turret gunners in desperate positions to figure out how to counter them meant the jet fighter had a future. The United States developed its own jet technology, yet the German equipment had much to teach American designers. The only real way for the United States Army to learn the secrets of the Me-262 and its axial-flow turbojet engines was to get one and study it intensely. That happened in Dayton, Ohio in 1945-1946 with an aircraft known as T2-711. In 2013, the National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s (NASIC) Office of History found the remains of that historic jet and began a research project to better understand its significance.

OBTAINING ME-262A-1 WERK NUMBER 111711

On 30 March 1945, German test pilot Hans Fay flew Me-262A-1 Werk Number 111711 from the Messerschmitt final assembly plant at Schwäbisch-Hall to Rhein-Main airfield at Frankfurt, Germany. It was the leading example of the world’s first operational jet fighter to fall into American hands. Intending to defect to Allied forces, Fay took off in the unpainted, factory fresh Me-262 on that Good Friday as a part of an effort to save the brand new aircraft from bombing attacks and advancing allied units. He planned to land near his hometown of Lachen-Speyerdorf, which recently fell to Allied troops and give himself up. However, he could not raise the jet’s landing gear. With decreased range performance changing his plans, Fay flew along the Autobahn at 300-400 feet to Frankfurt and landed on the only open runway at Rhein-Main at 1345. Allied troops only captured the field four days before.

Air Technical Intelligence (ATI) personnel led by Maj John Gette welcomed the German jet, and immediately began the initial exploitation of the Me-262. The aircraft featured a natural metal finish with black German crosses on the wings and fuselage and a black swastika on the tail. It carried those markings for its entire existence. The jet carried the numbers 711 in black on the tail and on the side of the bomb racks. Fay became a valuable asset as the expert on the aircraft and his interrogation on all aspects of the Me-262 began shortly thereafter.

The Army filmed the initial examination of Me-262A-1 111711 and photographed personnel climbing all over it. The troops opened every access hatch and studied the aircraft as much as they could, yet in order to obtain a complete understanding of the jet’s characteristics and potential usefulness it had to be shipped to the United States. The aircraft needed to go to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, where Air Materiel Command had the Army’s experts in foreign materiel exploitation (FME). After the initial few days of examination at Rhein-Main, the Army took the first step to get the aircraft home to the States. On 2 April 1945, the ATI personnel at Rhine-Main requested Mobile Repair Unit No. 4 from the 7th Air Depot Group’s 382d Air Service Squadron to come from airfield Y-34 at Metz, France to take the Me-262 apart for shipment. The crew of 14 men inspected the Me-262 and found the tools they normally used to take aircraft apart did not work on the German jet’s metric fittings. American ingenuity proved critical in overcoming that obstacle.

ATI personnel examining Me-262A-1 711 at Rhein-Main (US Army photo).

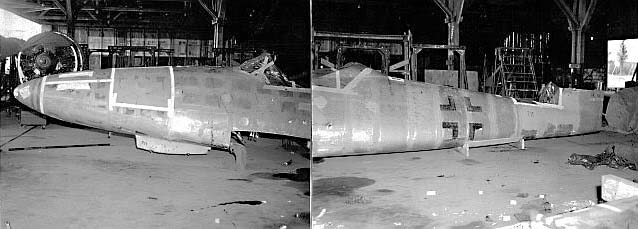

Me-262A-1 Werk Number 111711 at Rhein-Main after the defection (US Army photo).

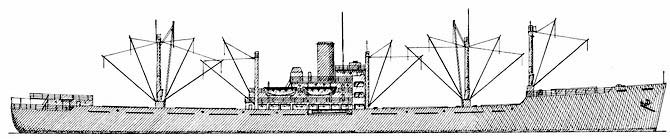

The 382d Air Service Squadron’s history recorded, “Under the supervision of TSgt Gordon R. Walters, Mobile Chief, the men, through improvisation and usage of old wrenches and tools found in adjacent areas, were able to accomplish their mission and disassemble the plane for shipment to the depot.”viii The team finished their job by 16 April 1945, when they photographed 711 in a disassembled state. In the coming weeks, the Army transported it to Rouen, France, where it departed Europe on 9 May 1945 aboard the Liberty Ship SS Madawaska Victory.

The fuselage after disassembly by the 382nd Air Service Squadron at Rhein-Main (US Army photo).

Dated 16 April 1945, this photo shows the disassembled wings of Me-262 711 (US Army photo).

Me-262 711 came to the United States on the Liberty Ship SS Madawaska Victory in May 1945 (Drawing by the US Maritime Commission).

TESTING AT WRIGHT AND PATTERSON FIELDS

After Werk Number 111711 arrived at Wright Field, a team from Air Materiel Command (AMC) re-assembled it, and by 29 August 1945, the aircraft stood ready for a test flight. Captain Russell E. Schleeh, a former B-17 pilot that became a leading test pilot at Wright Field’s Flight Test Division, took the aircraft up for the first test flight. The flight almost ended in tragedy when the assembly crew did not install the four, 130-pound MK-108 30mm cannons in the aircraft. The missing 520 pounds in the nose caused a major shift in the aircraft’s center of gravity (CG), causing Capt Schleeh great difficulty in maintaining control during takeoff. His skill enabled him to overcome the aircraft’s CG problem and he landed safely. Captain Schleeh’s first two flights in the Me-262 on 29 August and 12 September 1945, gave him one hour and 45 minutes experience in the aircraft. When Schleeh moved on to flight test other aircraft at Wright Field, other pilots including 1Lt Walter J. McAuley, Jr. from the Fighter Operations Section took over the testing of the Me-262, now known as T2-711.

Me-262 T2-711 in flight over Ohio, flown by Capt Russell E. Schleeh (US Army photo).

Air Materiel Command’s T-2 Intelligence accepted responsibility for the technical analysis of T2-711 and that resulted in detailed documentation of the jet’s capabilities. In February 1947, T-2 Intelligence produced a report on the Me-262 exploitation entitled, Evaluation of the Me-262 (Project No. NAD-29). In the report, T-2 engineer Roy W. Adams provided detailed analysis of the aircraft’s characteristics and performance. He explained that the tests involved the two examples of the German fighter still stationed at Wright Field; T2-711 and T2-4012. T2-711 served as the main aircraft for the handling and performance tests and flew 12 times for a total of 10 hours and 40 minutes. In comparison, T2-4012 flew eight times for a total of four hours and 40 minutes. During the 20 test flights at Wright Field during 1945-46, T2-711 required five engine changes and 4012 needed four. The crash of T2-711 on 20 August 1946 due to engine failure, as well as two single-engine landings by 4012, led to the cessation of the Me-262 flight test program at Wright Field. The limited value gained from further testing of a German jet was not worth the risk of losing a pilot.

Me-262 T2-711 sitting on the ramp at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio (US Army photo).

The Army Air Force team at Wright Field learned some important facts about the Me-262 in spite of challenges presented from both the early jet’s design and late war manufacturing shortfalls. The cockpit of the Me-262 tended to be tight for most American pilots, and it proved to be hard to turn around and see behind you and above you. The pilots graded the jet’s brakes as very poor and all takeoffs in the Me-262s had to be rolling takeoffs, with no stops. In addition, the landings rolls had to be very long. The Americans found the Me-262 did not handle well above 350 miles per hour, probably due to the fact that T2-711’s aileron trim tabs could only be adjusted on the ground. In that, Germany’s late war construction techniques manifested itself. The factory workers also riveted the elevator trim tab in place. The 12 test flights of T2-711 had to be enough to gain a greater appreciation for German jet development. It only lasted a year into the program.

THE LOSS OF T2-711

First Lieutenant Walter J. McAuley Jr. from Tarrant County, Texas loved to fly airplanes. With his country at war, McAuley received his wings on 29 July 1943 at the relatively late age of 26. At the time he piloted T2-711 on its last, fateful flight, he had 671 total hours, 61 of which came in combat. As a Wright Field test pilot, he accumulated two hours and 45 minutes flying the Me-262. The last test flight of Me-262 T2-711 began on 20 August 1946, when 1Lt McAuley avoided using the aircraft’s weak brakes by being towed to the end of the runway before starting his engines. He took off from Patterson Field at 1205 Eastern Standard Time (EST). Accompanying him was Maj Richard L. Johnson in a Lockheed P-80, tail number 44-85121.

The unpainted Me-262 T2-711 showed the German’s manufacturing techniques for the world’s first operational fighter. This is how it appeared on its last flight (US Army photo).

The two pilots planned to conduct a comparative formation performance test flight at 20,000 feet, where the two jets performed a power calibration side by side. Major Johnson flew his P-80 at full power as Lt McAuley opened up the throttle on the Me-262 and passed him. After completion of the test, the P-80 returned to the airfield as the Me-262 continued a high speed run over Clinton County, Ohio. Just as McAuley prepared to ease back on the jet’s throttle he noticed “a terrific vibration which could be felt and heard, developed in the aircraft.”

The Junkers Jumo 004 jet engines that powered the Me-262 lived up to their reputation that day. McAuley later testified, “We have been expecting it all along.”

The sequence of events that followed the vibration first had the pilot back the throttles off. Then, he noticed a surge in the right engine’s rotations per minute (RPM) gauge. Assuming the vibration came from the right engine, he closed the fuel cut-off valve, effectively shutting the engine down. Unfortunately, the vibration continued. McAuley reported, “At this point gray smoke was observed coming from the left unit and the left tailpipe temperatures went to zero, indicating that the instrument had failed.”

All he could do at that time was shut down the fuel flow to the left engine and place himself in a glider going 225 miles per hour. The left engine, Jumo 109-004, serial number 111301569, only had eight hours and 20 minutes on it since its last major overhaul. Now it was on fire. McAuley later stated, “I think the turbo wheel threw a bucket.”

Pilot 1Lt Walter J. McAuley Jr. (10 March 1917-11 March 1985)

The lieutenant realized he needed to let someone know what was going on. He called Major Johnson on the radio to come back in his P-80 and try to find him. He also called the air traffic control station at Patterson Field, WVAW-9, to provide him a heading to the runway. His next worry was trying to restart the right engine. In his crash investigation testimony, McAuley stated, “A start was obtained but the flame would not flare out and the engine continued to torch and run at approximately 2,500 R.P.M with flame extending two to three feet behind the tail cone.”

Given the normal operation for the engine was 8,700 R.P.M., he realized that the jet was going down. Johnson spotted the trail of smoke from the Me-262 when it was at 12,000 feet. He sighted the jet itself at 9,000 feet. Initially, McAuley told Johnson over the radio he planned to leave the aircraft at 5,000 feet if he did not start the engine. With a burning jet and no way to reach an airfield, McAuley chose to leave at 7,500 feet, with Johnson watching over him and giving him instructions.

After slowing the aircraft to 150 mph, the lieutenant pulled the canopy release handle on the right side of the cockpit. The canopy flew off and at 1240 EST the pilot jumped off the right side “to avoid the fire from the left unit.”xx As he flew under the right horizontal stabilizer, the back of McAuley’s head bumped the tail, knocking his helmet off. He continued to receive injuries when the opening parachute caused a buckle to cut his chin, and the landing in a corn field sprained his left ankle. He landed about a mile from where the aircraft impacted the earth. After McAuley bailed out the jet descended a little, then nosed up into almost a stall. McAuley observed, “It then nosed down and banked left and started a spiral steepening until the wings were near vertical at impact.” Including its first defection flight, Me-262A-1 111711 only flew 13 times in its short life.

FINDING THE CRASH SITE

The aircraft struck the ground on the edge of a road in Clinton County, Ohio. The impact scarred the road and created a large, deep crater full of wreckage. Several locals witnessed the pilot bailing out and the crash of T2-711. The story passed down to the landowners was that the Army took what they wanted, then dug a deep hole and buried the rest of the wreckage. The aircraft accident made the local newspapers, one of which stated the jet crashed two miles south of Xenia, near Highway 68. Another said it crashed “halfway between Xenia and Wilmington.”xxii Somewhere in rural Ohio laid the remains of the first German jet fighter to fall into American hands. More significantly, T2-711 served as the main test aircraft for the Army’s post-war assessment of the world’s first operational jet fighter’s characteristics and performance. Future American jet fighter design owed something to that airframe.

The inaccurate and vague descriptions in print made the crash site difficult to find for aircraft enthusiasts, and the wreckage lay buried for 67 years. Treasure Hunter’s Supply took on the challenge of locating the crash site and recovering artifacts from one of the most well-known aircraft in the jet-engine era. We began seriously researching the crash on 16 October 2013, with an email, and we were provided a complete copy of the crash report within a week. The most important clue found in the report was the “Place of Accident” block that included, “State, County, Nearest Town, Distance and Direction from Same,” which corrected the previously published crash location by over six miles.

On 23 October 2013, we conducted an investigative trip, yet located few possibilities for finding eyewitnesses to a crash that occurred in 1946.

Here is where we get a little fuzzy on details in this paper since we are still protecting the location of the crash of Me-262 T2-711, and have removed a few paragraphs which would clue one into the location of the crash site.

The critical element in finding the exact crash site of Me-262 T2-711 came not from a physical search, but from a photographic one. Upon examining the photocopied photos of the crash site, Mr. Paul Rich of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) offered his opinion that the telephone pole seen in the background of one of the photos was the key. He said, “They don’t move telephone poles, they REPLACE telephone poles…that one will likely still be there.” Given Mr. Rich’s advice, a new search began in the area adjacent to the nearest telephone pole on XXXXXXX Road, located on the other side of the home owner’s driveway from the original search area.

The crash site of T2-711 off XXXXXXX Road in Clinton County, Ohio (US Army photo).

A photocopy of the original photo from the crash showing the telephone pole across the road from the impact site (US Army photo).

The location of the telephone pole seen across the road proved to be the key in finding the debris field from the crash of T2-711. The pole in the foreground is a power pole to the house that dates to 1971. In this photo, Ron Hoffmann of Treasure Hunters Supply and In Search of History. (Photo by Robert Young).

Mr. Robert Young, the NASIC historian, conducting a metal detector sweep of the cow pasture identified as the crash site for Me-262 T2-711 (Photo by Ron Hoffmann).

On Tuesday, 3 December 2013, Mr. Ron Hoffmann and his research team coordinated with the landowner, and began a metal detector search in a cow pasture across the road from the telephone pole site. There in the pasture, we immediately began finding shattered metal debris from T2-711 about four to eight inches below the surface. The field of debris coincided with the impact area adjacent to the telephone pole seen in the photo-copied crash report image, just as Mr. Paul Rich suggested. As the team continued to obtain hits with the metal detectors provided by Treasure Hunter’s Supply it became obvious that the pasture held a large number of small, heavily damaged fragments. However, a high speed impact and the effects of farming scattered the debris over the years. The search uncovered a wide range of debris types and resulted in the team getting very muddy, although still clad in shirts and ties from our daytime jobs. We also had to avoid a large number of cow pies that existed in the debris field, although that did not diminish our excitement.

The first pieces of Me-262 that Ron Hoffmann and team located exhibited a heavy coating of dirt and in some cases, rust, typical of metal wreckage buried for 67 years. While twisted aluminum made up most of the finds, magnesium engine casing and steel turbine blades also came out of the ground, attesting to the fact that a jet crashed there. The metal detector identified the location of a possible fragment. Next, we used a shovel to dig up the section of sod holding the piece. After isolating the piece using the detector, we cleaned as much mud off as possible, then began an assessment of what we held in our hands. Several pieces in the field looked to be farm-related rather than jet-related, yet the vast majority of finds exhibited the extreme metal trauma caused by a high-speed impact.

Pictured are two turbine blades and a compressor blade from the Me-262’s Jumo 004 turbojet engines. The steel turbine blades exhibit rust (Photo by SSgt Mike Veloz).

After an hour, darkness forced us to suspend the excavation. That afternoon, we recovered 38 pieces of identifiable wreckage in an hour of searching after work. We reported our success to the landowner, and showed him the pieces of T2-711 found on his property. He remembered some men coming out with a metal detector years before. He never knew if they found anything. Nothing found on the internet ever indicated whether others succeeded in finding pieces of T2-711 prior to 3 December 2013. Mr. Dick Bogan previously stated that the father of one of the Senior Center members made off with a chunk of one of the engines after the crash and kept it in the barn. However, fearing that he might get in trouble, the family claimed that he got rid of it. The pieces of Me-262 lying on the landowners counter top represented the first confirmed remains of T2-711 to surface in 67 years.

Mr. Ron Hoffmann of Treasure Hunter’s Supply, pointing at the largest piece recovered on the first day. Located about five inches under the surface, the piece of aluminum wing included a fragment of tapered wing stiffener (Photo by Robert Young).

Mr. Ron Hoffmann holding the large piece of wing after unearthing it (Photo by Robert Young).

This is the large piece of Me-262 found on 3 December after going through a bead cleaner. The rivet pattern is exactly that of the Me-262 wing interior outboard of the engine nacelle (Photo by SSgt Mike Veloz).

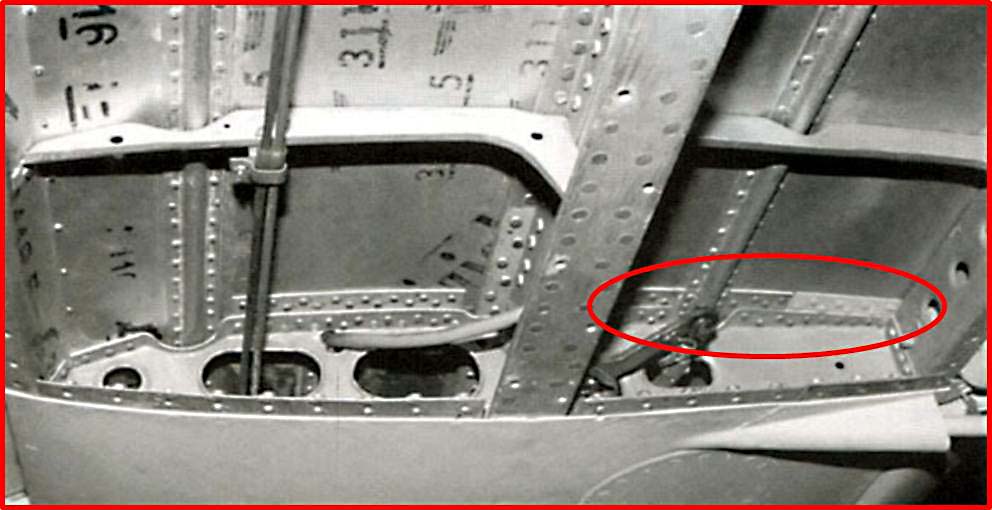

This photo shows the possible location of the large piece of Me-262 wing on the inside of an outboard section of wing, near the aileron actuator (Photo by John Bonanni).

The next day, Wednesday, 4 December 2013, we took the opportunity to return to the crash site and continue to search for debris from T2-711. The extended weather forecast called for heavy snow and extremely cold temperatures that threatened to completely shut down the search for more wreckage for the rest of the winter. We located 14 more pieces of the aircraft in the same general impact area. Once again, the depth of the discoveries varied from four to eight inches. Another compressor blade emerged, as did a large chunk of half-inch steel that puzzled all the aircraft analysts that later looked at it. That day, one of the most interesting pieces at first appeared to be a bracket for an oxygen bottle. That made sense given the Me-262 carried eight bottles to charge the aircraft’s four MK-108 30mm cannons in the nose.

Small pieces of Me-262 T2-711 located in the search.

With the help of Mr. Michael Anderson, lead mechanic at Legend Flyers LLC, the company that manufactured replica Me-262s in the state of Washington, a revelation came concerning the steel bracket. We emailed Mr. Anderson photos of some of the pieces discovered in the two-day search and he replied that the bracket belonged to the Me-262’s main landing gear. It attached the main gear door to the strut, enabling the gear to swing up and the door to follow it. He also confirmed the location of the large wing piece with the stiffener seen in the previous photos as “outboard of the engine.”i While a number of the fragments initially discovered went into a display case in the NASIC center’s cafeteria area, the question remained as to what to do with the rest of T2-711’s buried wreckage.

One of the artifacts discovered on 4 December was this bracket that attached the main landing gear door to the strut. The arrow points to the bracket. (Photos by John Bonanni – left; SSgt Mike Veloz – right)

Was the rest of the jet’s carcass underneath the cow pasture? The landowner’s son said that the story he heard was that the Army carried away what they wanted, dug a deep hole, and buried the rest. The landowners’ son then asked Ron Hoffmann and his team how far down the metal detectors could find metal. Mr. Hoffmann assured him that a good one could find the buried remains of the jet. The landowner then looked at us and said, “Let’s dig it up.”xxxii We then contacted Wright State University’s archeology department for technical advice, and made plans to dig up the remains of T2-711 in the spring of 2014. We also informed the National Museum of the Air Force of the find and told them that we might be able to make a significant donation to their collection in the near future. The museum had a display covering the story of T2-711 and that could be enhanced by remains of the actual aircraft.

SUMMARY

The Me-262’s contributions in World War II did not change the tide of battle, yet it did introduce the fighter world to 350 mile-per-hour overtake speeds, compressor stalls, flame-outs, wing slats, the scream of turbojets, and a total lack of engine torque. The jet’s 18.5 degree swept wings began a revolution, yet one of the greatest questions about the world’s first operational jet remained “what if?” Adolph Galland, Germany’s famed general of fighter aces stated in an interview, “I certainly think that just 300 jets flown daily by the best fighter pilots would have had a major impact on the course of the air war…This would have, of course, prolonged the war, so perhaps Hitler’s misuse of this aircraft was not such a bad thing after all.” That type of speculation is a part of the Me-262’s myth and legend. Historian Walter J. Boyne wrote, “The myth does a disservice to this remarkable airplane, which should be viewed entirely on its own merits; for what it was, not for what it might have been.”

Germany’s best surviving pilots took the advanced new fighter into combat, yet they represented an odd assortment of cast-offs and malcontents to the head of the Luftwaffe, Herman Goering. Because many fell out of favor with Goering and others suffered from combat fatigue, they almost slipped into oblivion. The emergence of the Me-262 gave them a chance to help defend their homeland in the final throws of a lost cause. The pilots of Jagdverband (JV)-44 became known as the “Flying Sanatorium,” yet represented one of the most highly experienced and decorated units in all the history of air warfare; truly a squadron of experts.

American pilots learned much from facing those gallant jet pilots in combat, yet more had to be done. For the U.S. to truly understand the significance of the Me-262, scientific and technical intelligence personnel, working with test pilots, needed to conduct an assessment on the aircraft. The aircraft that Hans Fay defected with in March 1945 gave the United States a better understanding of the world’s first operational jet aircraft. Other examples arrived in the States just after T2-711, thanks to Col Harold “Hal” Watson and his team known as Watson’s Whizzers. The fact remained that T2-711 began as the workhorse of the test program at Wright Field, and ended that way with more test flights than any other aircraft. The technical intelligence documents of 1946-1947 mainly showed images of T2-711, with its tell-tale lack of a paint job.

The most important thing for Treasure Hunter’s Supply, the NASIC History Office, and ultimately the National Museum of the Air Force, was that after 67 years under ground, the remnants of an aircraft that engineers and analysts authored the “Me-262A-1 Pilot’s Handbook” from can once again be seen and appreciated. The first German Me-262 jet fighter to fly in American skies was also a curiosity and a challenge for aviation enthusiasts for 67 years, and Treasure Hunter’s Supply and the Air Force History and Museum program accomplished something none of them did: We found it.